Japan has a way of making minimalism cosy. I’m not big on minimalism – unless it’s Japanese or perhaps even European Nordic. The soft and warm wooden tones, the faint scent of tatami. Rocking me to sleep. There is something quite comforting about sleeping so much closer to the ground. Our natural cradle, perhaps. So, sleeping on a futon didn’t feel unnatural at all. Many times I feel the urge to just lie down on the floor in my everyday life.

But that was just my first night in Kyoto. A stay in a Ryokan is pricey, so I’ve spent the remaining nights at Tune Stay Kyoto. Just a standard, practical accommodation, close to the station.

After dropping off my bags I headed to West Kyoto. My day was going to be focused on the West and Northwest parts of the town. Which probably ended up being one of my favourite days in Kyoto.

Kyoto is famous for its wonderful temples, the historical streets, the memory of an Imperial capital stitched in so many corners. But Kyoto to me stands out in my memory by its wonderful nature. Moreover, how nature so easily cohabits with the temples around, as if accepting of its sacredness. My favourite thing about the Japanese is precisely the constant attention to the cycle of living things, of attempting not to disturb the natural ways, but simply build around it.

To me nature is sacred. It’s where I find my spirituality. It’s what we should adore – perhaps similar to Shintoism, I’ve always been conscious of being surrounded by so many living things. The trees, the plants, the bushes, the moss. The wildlife, the little insects, the chirping of birds, the flap of their wings. Even the sound of a creek. It’s a life that is slow, that is unbothered, that simply exists, in the moment. It doesn’t ask anything from us – just that we don’t destroy it. There is nothing that makes me calmer than Nature. And there is also nothing that makes me more furious than its destruction.

When I headed to the famous Arashiyama Bamboo Grove, I knew what I was going to find. Crowds, worried about taking the perfect IG picture, instead of actually look in veneration at the beauty of those tall Bamboo trunks. And of course – the vandalism. Seeing the Bamboo carved. It’s of such arrogance, for humans to just think they have the right to leave a mark, by hurting another living being. My visit to the Groove was quick.. I couldn’t quite stand it, if I’m being honest.

In October, I was just in that moment when the greenery is still lush, daring, and lively, but autumn is showing its signs. I was hunting for these… I love to see the seasons changing. I particularly like it because it happens slow enough for you to notice, but also fast enough to be easily missed. Noticing it means you are allowing yourself to slow down and pay attention. It’s a little exercise I like to do, even back in London, when life is so busy I often feel I’m living inside my mind. But we also go through seasons – and I’ve noticed mine align quite well to those of nature. Because again, I’m her daughter. We all are. We should be reminded of that.

I walked North, leaving those crowds behind. Surrounded by heavenly nature, I was leaving that bad taste in my mouth. Embraced by greens, breathing the purity of air so nicely maintained by all of that forest. Until I came across the entrance to the Jōjakkōji Temple. It was not planned for me to visit. But something pulled me in, perhaps the fact that it was so empty. I paid my ticket. And wow. The peace. The quiet. A temple that seemed to have been built by Nature, not by humans. Grounds covered in mossy tapestry, paths framed by maple trees, still green but changing.

I spent some time here, finding myself at peace. There was a remoteness to this place that was difficult to understand – not that far the crowded Arashiyama, and ahead some other famous temples, with so many tourists. I kept wondering how am I here alone? But feeling so grateful to be so. To have that beauty all for myself. No extravagant, luxurious structures. Nature did it all.

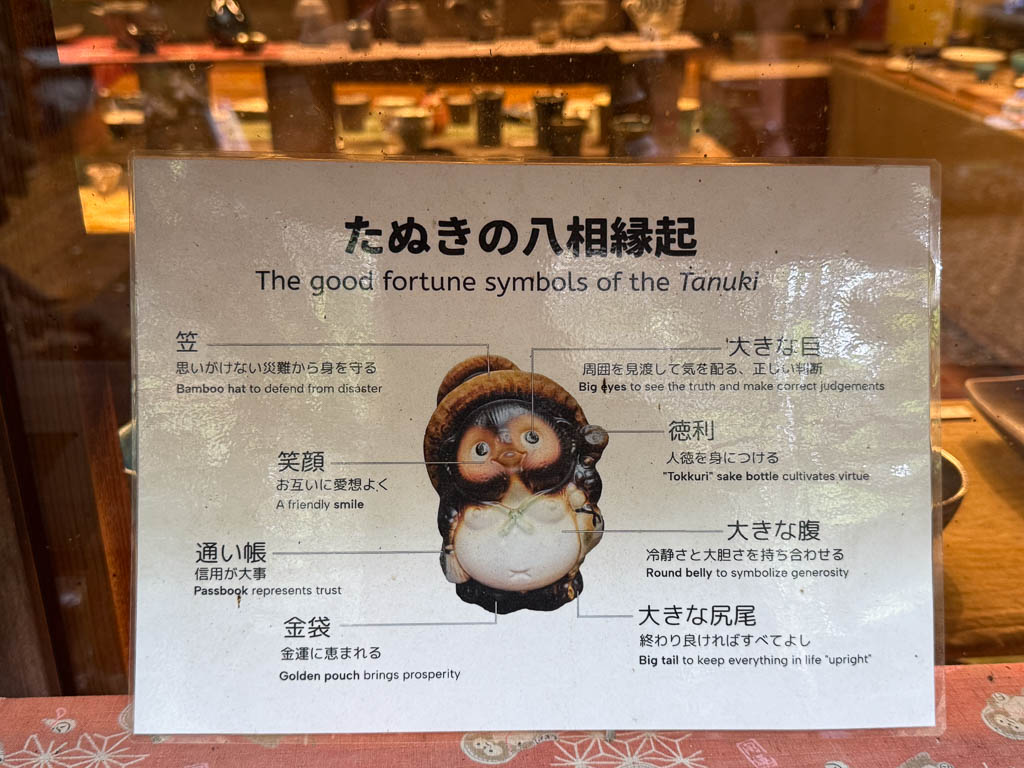

It was in these parts of Kyoto that I came across yet another good luck charm – Tanuki. These are ceramic Japanese racoon dogs representing prosperity and good fortune. I often saw them at the entrance of shops – it’s adorable, and every single part of it has a different meaning, which is fun to learn about.

After this wonderful moment of pause, I kept walking, coming across many Tanukis, but even someone’s garden with a Hello Kitty Jizo – a pop culture mashup with ancient Japanese tradition. Just something else about Japan – they never take things so seriously as to not allow the new/modern to mix with the old. In fact, the new often takes inspiration from the old, ensuring tradition is alive and surviving, adapting to the present day. Traditionally, these small stone statues represent Jizo, one of Japan’s most beloved deities, considered as the guardian of travellers, children and expecting mothers.

This is one of the best things about walking, rather than taking a bus or even renting a bike. I was able to see all of these little details, which I find give me a deeper understanding of the culture I’m a visitor of. Plus, this part of Kyoto was surprisingly so empty. I was walking on the Saga-Toriimoto preserved street, seeing just few other tourists doing the same. Perhaps those with the same mindset I have – let’s walk whilst our legs allow.

My next stop was the Adashino Nenbutsuji Temple. Once again this temple was a lot emptier of tourists than I would have imagined. It’s so unique, with its field of statues. The central area is home to approximately 8,000 stone Buddhist statues and miniature pagodas. These markers were once scattered across the surrounding hills as this area was, for many years a site, for “fuso” or “wind burial”. This was a practice where the bodies of the poor, nameless and those without family were simply left in the hills to be claimed by the elements. As Buddhism became more established, locals or travelling monks would place small stone Buddhas at the spots where remains were found.

For hundreds of years, these were forgotten, often buried in the woods and fields. It was only in the Meiji period (around 1903) that locals and temple officials made an effort to gather the stones. Now,in late August, the Sento Kuyo (Thousand Candle Ceremony) is celebrated with thousands of visitors lighting candles for each individual statue, ensuring that even those who died without kin are remembered and lit on their path to the afterlife. A proper honour to the deceased. This is why this place feels so special. Thousands of lost souls, together, and not forgotten.

At the back, there is a peaceful and serene bamboo grove that is a far cry from the busy Arashiyama.

On my way to my next stop, I came across charming houses topped with some sort of dark straw roofs. This is a traditional Japanese style known as Kayabuki. Kaya is the term used for various species of tall grasses – these roofs can be found here because this is a designated preservation district, keeping the atmosphere of a traditional Meiji-era merchant town. In fact, replacing these roofs can cost over $100K and this has to be done every 20 years. So this might be one of the only places where you can see it – yet once again proving my argument defending walking as the best way to explore Kyoto.

The Otagi Nenbutsuji Temple was my last stop around this area. There is a bus that takes you directly here. It’s not very frequent, but used a lot by tourists – and I arrived at the entrance of the temple precisely when a bus had just stopped, from which an ocean of tourists came. This was unlucky… and in fact this place turned out to be a lot busier than I expected, despite being quite far out from the city centre.

Yet, it’s wonderful. It could be compared in many ways to Adashino Nenbutsuji, but whilst the latter is a lot more solemn, this one is almost lighthearted. There are over one thousand Rakan (Buddha disciples) statues. These were carved by amateur volunteers in the 1980s under the guidance of a head priest who was also a master sculptor. Precisely because of this, you find some modern representations – I noted a couple that made me smile – one holding a pug and another one with a camera.

I thought about taking a bus back to town. I was starting to get hungry. But the time I would be waiting for a bus (crowded one) was the same of just walking all the way back down, and since the walk was so nice, I ignored my tired legs and walked a bit more. Ended up getting lunch at a little traditional restaurant, sitting on tatami and low tables. The place isn’t on Google Maps – at least I could not find it. The food, the ambiance, the staff… fantastic. It was the perfect place to rest, reenergise and plan my afternoon.

Finally, I started my afternoon. First by going to a place that is very special – all were, but this one personally – because when I entered the main hall of Ryōan-ji I came face to face with a little artwork that said “When I change, the world changes”. At many times in my life, I’ve struggled with depression and the ways I try to not to go back to such a state is precisely by changing the way I’m facing the world and mny own dark thoughts, forcing myself to look at things and experiencing them differently, as hard as it it sounds – and is. This is a practical application of Zen, precisely what this temple is famous for. It’s a UNESCO World Heritage site, originally an aristocrat’s villa, it was converted into a Zen temple in 1450. Its rock garden is what makes this place so famous, considered the pinnacle of Japanese Zen garden design.

The garden considents of 15 stones of various sizes arranged in five groups on a bed of meticulously raked white gravel. The stones are arranged so that from any vantage point on the temple veranda, at least one stone is always hidden from view. In Sen philosophy, the number 15 symbolizes perfection, so the inability to see all 15 stones at once suggests that human perspective is inherently limited and somehow flawed.

Personally, I found it stunning. My body resonated with the calm, simple, minimalist garden. I sat there, observing the stones, noticing my own perspective. Reflecting on how we all live different truths and different views of the world. How a life can take on so many meanings and experiences only based on that one flawed individual view. And how I am often such a tragic victim of my own view.

There is something very special about the washbasin (Tsukubai) located behind the priest’s quarters. I had learned about it during my stay at the Ryokan, where they had a replica. It’s shaped like an old coin, and it bears an inscription that translates to “I learn to be content”.

I used to repudiate this idea. Of contentment. I used to think this was a sign of ambition lacking. Of accepting destiny, and just letting things happen to you, very stoic. But I’ve learned especially whilst travelling in Southeast Asia that you don’t have to choose between ambition or contentment. In fact, contentment is about enjoying the journey, honouring what you’ve got. It doesn’t have to mean you won’t have goals. It just means that the important thing isn’t to achieve them necessarily… because happiness is found in the everyday. It’s about recognising what I already have. And this goes really well with “when I change the world changes” because contentment is that change. It’s not about I need things to be different but instead what I have, what I am is also enough right now.

To me this is the most beautiful lullaby. It comforts me. My mind kept whispering these teachings to me, whilst I explored the grounds. Forest, a huge pond. Was that even real?

To end the day I visited the famous Golden Pavillion – Kinkaku-ji – a great contrast to serene, humble Ryōan-ji. If the latter is calm, silent, minimalist, Kinkaku-ji is there to impress with light and brightness, a little vanity, a bit more materialistic. The top two floors are completely covered in pure gold leaf, and the pond was designed precisely for the sharp, perfect reflection of the gold in the water. This place is a bit narcissistic this way – and in fact, it sort of led to a tragic event.

In 1950, a young monk set the entire temple on fire, burning it to the ground. This act wasn’t driven by hate – he felt the temple was so perfect, that it made his own life feel unbeatable. The temple was rebuilt in 1955, standing today as a reminder that perfection is in fact fragile, but it’s the ability to rebuild where the strength lies.

Once again, it was almost as if I was walking through my own unconsciousness. Of what happens when we let our demons convince us that we aren’t enough. In fact the fact that the first floor, the foundation, is plain wood – that’s the perfect metaphor to life. Our foundation, the “plainness” of everyday life. The top floors, covered in gold, our golden moments in life. But you need both – it’s all about balance.

Love, Nic

P.S. The below are affiliate links. This means I may earn a small commission if you decide to purchase or book anything through these links. None of it is sponsored. All my recommendations are based on my lived experience.

Where I stayed in Kyoto: Tune Stay https://booking.tpo.lv/6724knY6

Truly Sim Card: Get 5% Off with code wingedbone (https://truely.com/?ref=aff_thewingedbone)

This was such a beautiful, reflective read. I love how you connected Kyoto’s temples and nature to your own inner journey. The contrast between Ryōan-ji and Kinkaku-ji, calm minimalism vs golden brilliance, was described so perfectly. And that quote, “When I change, the world changes,” really stayed with me. Kyoto, through your eyes, feels deeply personal and inspiring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person