It’s no surprise that my favourite part of Krakow – or perhaps the place where I would see myself spending the most time if I lived there – is precisely the most bohemian looking, with scrappy and somehow gritty streets, full of vintage shops, galleries, street art and graffiti, contrasting with cute and stylish cafes and bars. That describes the neighborhood of Kazimiersz in Krakow. But there is so much more to it than style and vibes. There is history, and I will tell you a little bit about it.

You’ll find that Kazimierz is often labelled as the Jewish Quarter – but the reality is a lot more layered, as it often is. Once upon a time, all the neighborhoods surrounding Krakow were independent cities in itself – and Kazimierz was one of such cities. Its name comes from its founder, King Casimir the Great (Kazimiers Wielki in Polish). He erected the city in the 14th century, with the main purpose of creating a new layer of protection to Wawel (the royal city) from the southern side (aka, creating distance between the potential enemy and the castle).

.fixed-gallery { display: flex; justify-content: space-between; gap: 12px; } .fixed-gallery img { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 8px; transition: transform 0.3s ease, box-shadow 0.3s ease; box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0,0,0,0.1); } .fixed-gallery a { flex: 1; } .fixed-gallery img:hover { transform: scale(1.02); box-shadow: 0 4px 16px rgba(0,0,0,0.2); } @media (max-width: 600px) { .fixed-gallery { flex-direction: column; } .fixed-gallery a { width: 100%; } }

All of the neighbourhoods outside of Krakow used to be independent cities, and Kazimierz was one of them. But it was only in the 15th century that the Jews moved here – or shall I say, were forced to resettle, from the Krakow city centre. Around this time, all over Europe, there was a wave of anti-semitism. The origins for this are, as usual, murky – but it’s a story as old as time, and we all know what it really comes down to – wealth and power. The Christian wealthy merchants looked at the Jewish as additional competition. Conveniently, a fire in 1494 destroyed a great part of the city, and guess who was to blame? You guessed right. The Jews.

.fixed-gallery { display: flex; justify-content: space-between; gap: 12px; } .fixed-gallery img { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 8px; transition: transform 0.3s ease, box-shadow 0.3s ease; box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0,0,0,0.1); } .fixed-gallery a { flex: 1; } .fixed-gallery img:hover { transform: scale(1.02); box-shadow: 0 4px 16px rgba(0,0,0,0.2); } @media (max-width: 600px) { .fixed-gallery { flex-direction: column; } .fixed-gallery a { width: 100%; } }Having no other options, the Jewish established in the allocated quarter of the city of Kazimierz, which ended up being walled up. This was somewhat imposed by the authorities, but also accepted by the Jewish leaders for safety reasons – a wall will help the outside powers control the movements of the Jews, but it would also protect this community from the animosity from the Christians.

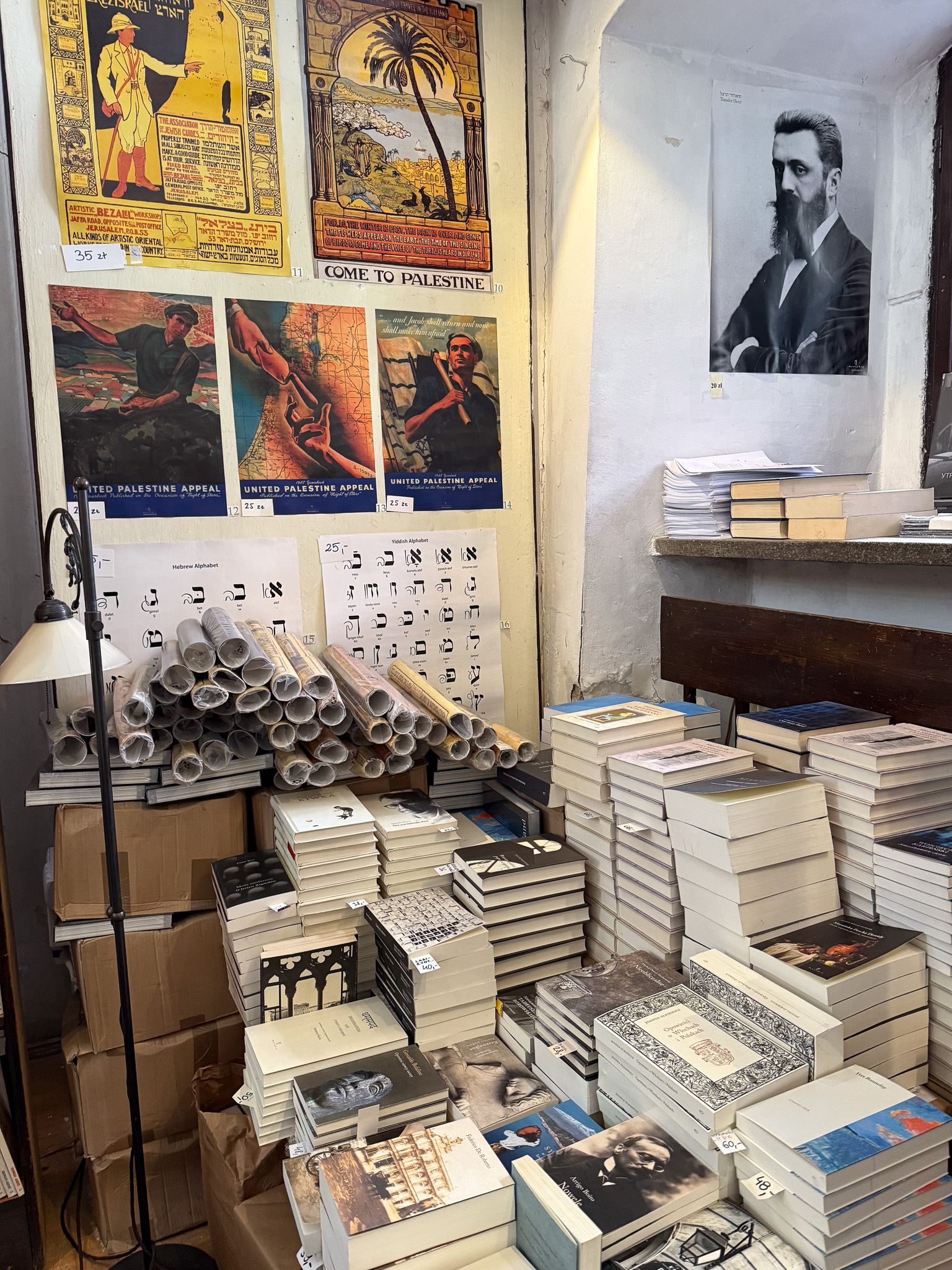

Within these walls, the Jewish, as they always seem to do, prospered. The centre of the Jewish quarter is today’s Szeroka Street, where you’ll find synagogues, Jewish schools, academies and institutions. For centuries this was one of the most important cultural Jewish centres in Europe.

The walls were dismantled in the 19th century – more precisely in 1822 – when Krakow and Kazimierz were merged into one city under Austro-Hungarian rule. This made it possible for Jews to settle all over the district and in the 1930s they constituted a quarter of the population of Krakow…until World War II.

This was when the Jews were expelled from the city by the Nazis, and forced to move to what was known as the Krakow Ghetto in March 1941. The Ghetto was located in Podgórze, across the river from Kazimierz – a divider in itself. The Nazis were experts in utilising symbolism against the Jews, but the river wasn’t enough. The Ghetto was walled, and the walls were shaped like Jewish Tombs. It shows how thoroughly the German Nazis thought about the best ways to humiliate, oppress and segregate the Jewish. Just about a century later, the Jewish of Krakow were again within walls – but this was death shaped. A premonition for what was about to come.

Imagine, being forced out of your home, where you raised your family or are about to raise one. Where you grew up or are growing up. You try to bring something with you. Of emotional value, priceless, others with a price tag for future insurance. You don’t really know where you are going. So you bring some furniture, hoping to make the unknown a home, a beacon of light in the darkness of the times. And then, once you get there, you are allocated the same tiny flat as four more families. There is barely any space for you; there is no space for your furniture. A lot of it was dumped in Plac Bohaterów. This is where the daunting Memorial of the Jewish Ghetto can be found.

The memorial is terrific in its simplicity – empty chairs, in straight, somehow severe lines, facing the direction outside of the city – almost a calling for the outsiders to see what happened there. Or perhaps pointing to the direction the Jewish were being pushed to – out and out, out of Krakow, out of Poland, out of the world of the living. The empty chairs remind us of the simple, ordinary lives cut short by hatred. Stolen lives both figuratively and, sadly, literally.

In the movie Schindler’s List the Ghetto part was actually filmed in Kazimierz, and you can visit the Schindler’s List Passage (now taking the name of the movie). If you have a good memory (I do recommend watching or rewatching it just before the trip, you’ll see this is where the scene where a Jewish child who was working for the Nazis saves a woman and her daughter from being found, when he sees this woman was his teacher.

If you have the time, I highly recommend this Jewish Walking Tour. It covered Kamiziers, Jewish Ghetto, and the Christian side of the district of Podgórze where you can also visit the beautiful Church of St. Joseph.

I have to say that it is so easy to forget these streets and these walls were witnesses to such cruelty. When I travel, I think it’s important to be a testimony to these moments in history – even if these make me grieve, cast a shadow on a sunny day, and are uncomfortable, make me twitch, make me want to look away.

These days, the city is bursting with vitality. From the old town of Krakow, to Kazimierz and even the space once occupied by the Ghetto. Kazimiers particularly. Since I was there during the Easter weekend, I couldn’t truly explore the many shops and restaurants in this part of town, as many closed or operated in limited hours during the festivities. From my perspective, this is actually the best place to potentially come for nice meals and drinks – it’s less busy than Old Town Krakow, less touristy, and you can truly enjoy some unique spaces (below Hevres Bar).

.fixed-gallery { display: flex; justify-content: space-between; gap: 12px; } .fixed-gallery img { width: 100%; height: auto; border-radius: 8px; transition: transform 0.3s ease, box-shadow 0.3s ease; box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0,0,0,0.1); } .fixed-gallery a { flex: 1; } .fixed-gallery img:hover { transform: scale(1.02); box-shadow: 0 4px 16px rgba(0,0,0,0.2); } @media (max-width: 600px) { .fixed-gallery { flex-direction: column; } .fixed-gallery a { width: 100%; } }Love, Nic

One thought on “Kazimierz & the Jewish History of Krakow”