It was 11am and I was absolutely overwhelmed. I had arrived in Phnom Penh just the night before, and checked in a pretty poor hotel. My room was located just next to the reception, on the ground floor, it definitely hadn’t been properly cleaned, and there was music blasting from their bar/restaurant literally for the entire day and most of the night. The staff was incredibly unwelcoming and dismissive. I dropped my backpack on the floor feeling disheartened. How did this hotel have so many good reviews, high scores? It also did not feel safe. Looking back I should have just picked up my bags and leave, to find another place, but I only had two nights scheduled in Phnom Penh, had arrived late at night…was tired, and sometimes that feeling wins.

I had been travelling for about ten days then, and I was about to have my first serious anxiety attack, questioning my whole decision to embark on this trip, and for the very first time considering cutting the trip short. Perhaps I had overestimated myself. Maybe I couldn’t handle the cultural shock. Maybe I couldn’t handle the discomfort. And being alone, by myself, I started to spiral, falling knee-deep into muddy sands, looking up to see murky skies. This is something I tend to do. I get obsessive over specific things, can’t stop thinking about it, trying to find answers and feeling a growing sense of intense despair.

These were the thoughts I was having at 11am, after coming back from a painful walk in the city. I ended up developing an intense and perhaps unfair dislike for Phnom Penh. I couldn’t wait to get out of there. Perhaps as well because most people I found were also not nice. Haven’t I read Cambodians were incredibly kind and welcoming people? Really don’t trust everything you read.

Walking in Phnom Pehn

My main goal in the city was to visit the Genocide Museum. It was about thirty minutes walk from the hotel where I was staying, which shouldn’t be that bad, especially if you go early, before the sun shines its brightest and deadliest rays. I didn’t want to go into bargaining prices with tuk-tuk drivers. But once again the reality of how these cities are just not walkable hit me hard – zebra crossings are rare, and when there are traffic lights for pedestrians, I swear they seem to be playing a prank on you – it takes ages for green to come, and when it does, it’s only for a few seconds. And it is not certain that you’re safe to cross – drivers don’t respect it. The sidewalks are obstructed with motorcycles and cars parked on top of them, and sellers use the space to set up their stands. Similar to HCMC, you also have to watch out for your step, or else you may trip on a loose stone, or break your foot on a hole. And should I mention the air and noise pollution? It was worse than HCMC. As someone who is very sensitive to smells, the stench was horrible. From the smoke of bikes that likely should have been sent to the scrap yard years ago, to the stench of rubbish and sewage. At some point, I did think I was going to pass out. I started to miss Europe, badly.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the very dark and cruel past of Cambodia

Eventually, I arrived to my destination – the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. And at some point, I thought I had gone through that walk from hell for absolutely nothing. In Cambodia, the official currency is the Cambodian Riel, but in reality they mostly accept US Dollars, which makes it all very confusing. Knowing this in advance, I had brought with me US dollars, but I only had $100 bills. Well at the museum they did not only have change for that $100 bill, they also didn’t accept card payments. The woman at the desk was also not nice or accommodating at all, telling me that only later on in the day they might have the cash to give the change. I had not walked for almost 30 minutes for this. I asked then if there were any ATMs nearby, hoping I could get some smaller bills. When I go to the ATM the first information displayed is that it only provides $100 bills. So then I decided to withdraw riels and thankfully that worked out fine. I did have to go back to the museum, ask if the accepted riels and how much was it in riels (often prices are only displayed in US dollars too).

The start of my visit wasn’t the most auspicious, but it was about to get worse. Of course, it was – because visiting a Genocide Museum will never be an easy thing to do. And also because I had made a serious mistake by not paying $5 more for the audio guide. There aren’t any explanations written anywhere. I just wished the lady had told me that the use of the audio guide was highly recommended. I just thought it was quite pricey – if the ticket for entry is $5, the audio guide shouldn’t cost an extra $5. But I was learning that even though Cambodia is quite cheap when it comes to food and accommodation (for the foreigners of course), for access to its culture you pay well. To be fair to them, Cambodian citizens can often enter for free, and have reduced prices for things like audio guides. I suppose we foreigners pay for both, as the entry prices to major landmarks often are equipable to those prices you find in Europe. Unfortunately, you do get less, with facilities in disrepair and again not any explanations can be read anywhere.

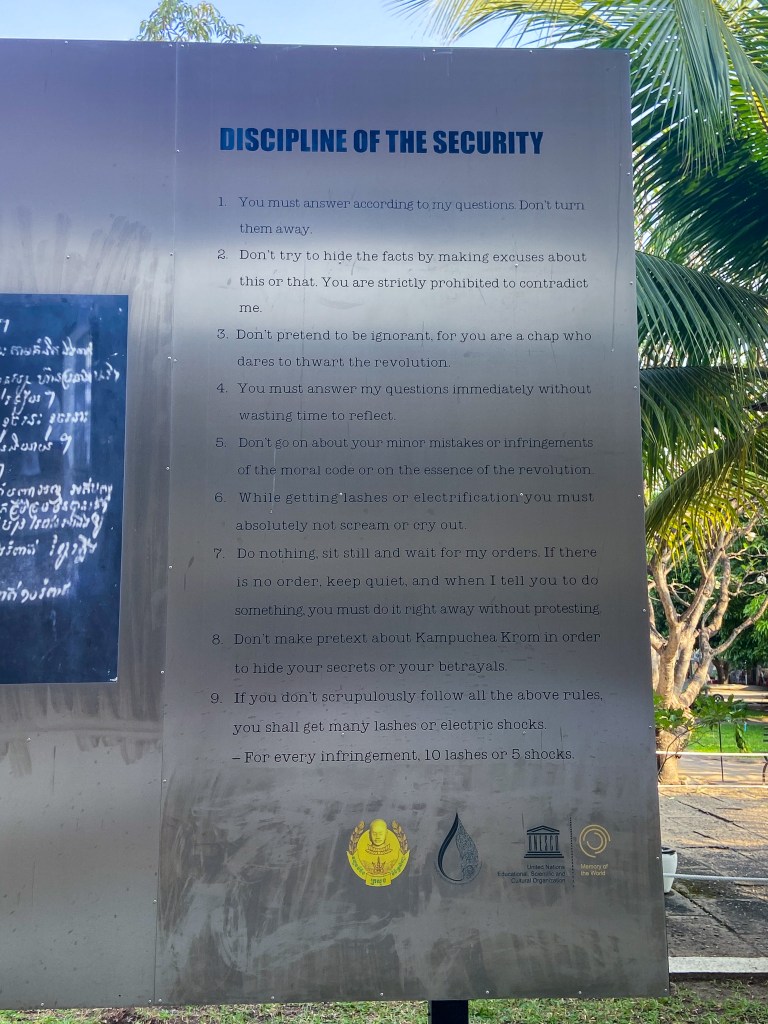

Whilst I did regret not going for the audio guide, I have to say that not a lot of explanation is needed when you see barbed wire covering balconies to stop suicidal prisoners from jumping, when you enter rooms furnished with iron beds with cuffs for wrists and calves. When you see pictures of hundreds of faces belonging to innocents, who were imprisoned and tortured, meeting a gruesome end. Or when instead of their pictures, you see their skulls. Hundreds of them.

Only humans can be this kind of evil. Capable of committing such atrocities to one another. One wonders how. My skin was crawling in repulsion, and my throat was tightly knotted.

I didn’t get the audio guide, but I had done some homework before coming to Cambodia, dimly aware of its terrible recent past. I read the book First They Killed My Father by Loung Yon, a first-hand account from a survivor of what happened between 1975 and 1979 – four years of terror in Cambodian lands with thousands of its people sent to what became known as the killing fields. A movie based on the book was produced by Angelina Jolie, but I haven’t watched it.

It is estimated that 2 million people (about 25% of Cambodia’s population at the time) were killed by the Khmer Rouge, the members of the Communist Party headed by Pol Plot. This is one of the reasons why today’s population is so young – about 65% of Cambodians are under the age of 30 years old.

With the goal to turn the country into an agrarian socialist republic, after taking power in April of 1975, the Khmer Rouge forced everyone to move out of the cities and murdered any citizen with higher education – journalists, intellectuals, students, doctors, lawyers – but also those who belonged to Cambodia’s previous military and political leadership, business leaders, as well as those with religious affiliations, Buddhists, Christians, Muslims, and mixed raced Cambodians, specifically Chinese Cambodians. Plus, you were considered guilty by association – meaning entire families, children and babies included, were cruelly killed by the Khmer Rouge. Often families tried to hide their identity to survive, which was the case with Loung Yon’s family. Cambodians were relocated to what were in fact forced labour camps in the countryside, where they were subjected to torture, malnutrition, and just outright killed. Disease was also rampant, and the lack of doctors and any kind of medical care led to it being one of the big causes of death. It is estimated that while 60% of deaths during this time were direct murders, the remaining 40% were from illness and starvation.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is located in what first was a school and then became Security Office 21 (S-21) in the then abandoned city of Phnom Penh. It was a prison, used for detention, interrogation, torture and murder of all of those that were considered enemies to the regime. No one was ever released. Once Phnom Penh was liberated, in 1979, only twelve inmates had survived. Four of them were children.

Located in the outskirts of Phnom Penh were the killing fields, a place where some of those who had survived torture in S-21 were sent to be executed. You can also visit this place, but I must confess after visiting Tuol Sleng, I couldn’t stomach more of it in the same day. I have a pretty vivid imagination.

Getting some “fresh air”

After this visit, I tried to get distracted and walked a bit more around the city. But my heart just wasn’t in it, and as the sun was going up, I started to feel physically sick, and unfortunately had forgotten my hat in the hotel. Trying to find shade wherever possible, I still forced myself to walk around, instead of ordering a ride. I was going to leave the city the next morning, and it seemed somehow a waste that I wasn’t seeing more of it.

I was learning that when you travel long-term, you’ll have bad days. Days when you just don’t feel like exploring, days when your body for some reason is not at its best. Exactly as it happens when you’re getting on with your normal daily life, back home. So I decided to give myself a break. I still considered visiting the Royal Palace, but the tickets were not cheap and to be honest I didn’t want to spend so much money visiting a place that didn’t really mattered that much to me. Plus, I was seeing so much poverty on the streets that the contrasts were even making me feel sicker. At this time, I was still adjusting to this reality in South East Asia. It’s not something you get used to, but perhaps you end up getting desensitised to, which is awful to say, but nevertheless true. After a few more weeks, I’d be sad with the reality, but somehow the pungency of it got to me less and less. It had to, otherwise I couldn’t have gone through these four months in SEA. But it wasn’t easy… especially when you are as sensitive as I am.

I did a quick visit to the Central Market, mostly for its architecture (I wouldn’t count on it for souvenirs) and then to the tallest temple in the city, Wat Phnom Daun Penh, where I stopped for a while to observe the locals in their religious practices. There is a very nice greenery around it, where you’re protected from the harsh rays of the sun.

After that, I walked alongside the Tonle Sap River for a while, watching it joining the Mekong River, and thinking how this could be a much nicer walk if there was many green, any shaded spaces. Still, the vision of open water, somehow, calmed me a little. But I knew I couldn’t keep going for much longer. For some reason, something in me wasn’t agreeable to Phnom Pehn. Perhaps my mental state, aggravated with the visit to Tuol Sleng, and the terrible walk in the morning, and the sights of poverty in the streets, and a twinge of cultural shock… it was a cocktail for disaster.

For the rest of the day, I stayed at the hotel, in their outdoor area which was nice despite the loud music, and changed the hotel where I was going to stay in my next stop, Siem Reap. I wanted to make sure I was going to get a clean room, hopefully with windows, and and that I felt safe. I had been going for very basic, budget-friendly hotels – so I booked my next stay at a brand-new Ibis Styles in Siem Reap. It was of course a lot more expensive than what I had booked initially, but I know till this day it was the best decision I made for myself. I cannot express how much better I felt after my first night in Siem Reap. But I’ll save that for the next post 😉

Love, Nic

5 thoughts on “Phnom Penh: Walking Ordeal and the Challenging Visit to Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum”